This is the third of three posts about the planetary protection workshop I attended at NASA Ames from March 24-26, 2015. The first is here.

I mentioned, in my last post on forward contamination, that reverse contamination is the primary concern for Planetary Protection (PP). In this context, reverse contamination refers to the transport of Martian life to Earth. Although, I did hear a totally different definition from Jen Law (the current flight surgeon for the ISS,) which I will get back to later.

I totally get why the primary mission of Planetary Protection is to, well, you know, protect OUR planet. After all, life on Earth has a very long history of ensuring the survival of life on Earth. But, from my perspective, it seems like less of a concern than forward contamination, which all seem to agree is inevitable. It’s tempting, as someone whose job is NOT to contribute to policy on this topic, to roll my eyes when people in the room suggest that astronauts returning from a Martian collecting trip might show signs of illness due to infection by a Martian microbe. First of all, see previous post for the extreme survival skills required to get by on Mars and then ask yourself: what are the odds that something adapted to life on Mars is likely to become a human pathogen upon first contact? Not very? Really, no one has idea. But, let’s assume that a Martian microbe actually has infected a human astronaut, and we have a sick astronaut on a long flight home, then ask: how would we attribute the illness to the Martian microbe? Are we going to apply Koch’s Postulates during the return voyage? Are we going to do some high-throughput 16S rDNA surveys or metagenomics? If we do, will we find evidence of familiar human pathogens. Of course we will. Wait, do Martian microbes even have DNA? It must be the case that other Planetary Protection workshops will be addressing these issues, because every time I brought them up people were like, “Yeah, yeah, we know that stuff is important and difficult.” But, no talks on these subjects at this workshop. Maybe next time!

So, with respect to avoiding reverse contamination, the main objective is to, as they say, “break the chain” (BTC) of contact with Mars. Bob Gershman discussed the technology under development to meet this objective for a robotic Martian sampling trip. According to the NASA procedural requirements (see NPR 8020.12), “Samples returned from Mars by spacecraft should be contained and treated as though potentially hazardous until proven otherwise.” How contained is contained? The PP Office has a “draft” requirement of < 0.000001 probability of inadvertent release of a single unsterilized Mars particle to the Earth’s biosphere. I MEAN. How the hell do you make that calculation!? What’s really cool is that they will actually figure that out.

So, anyway, there needs to be the sealing of compartments and the external sterilization of components and the withstanding of very unpleasant Earth re-entry conditions, including extreme heat and force. Gershman presented a very detailed, technical account of various sealants and containment materials and reentry technological developments. I was relying pretty heavily on my audio recorder for this talk, because it was too information-dense for me to take useful notes, but it died. So, I’ll share with you an excerpt from his abstract.

“Sealing modalities being investigated include brazing, explosive welding, bagging, and conventional o-rings. Sterilization modalities include heat, pyrotechnic paint, plasma, and hydrogen peroxide; but it should be noted that NASA has not yet considered which of these – if any – could be certified for sterilizing Mars material. Also, technology is needed to assure (with an unprecedented degree of confidence) that the Earth entry vehicle would withstand the thermal and structural rigors of Earth atmosphere entry and that the sample container and its seals would survive Earth entry, descent, and landing. Concepts for a new Earth entry vehicle that could satisfy the stringent MSR reliability requirements have been under study for several years, including some preliminary technology development activities.”

So, basically, we’ve thought a lot more about forward contamination because that draws upon our understanding of sterilization and contamination in the context of human health and microbial monitoring, a la CDC, DHS, DOD, etc. The procedures and technologies for dealing with safely bringing Marian life to Earth are very much under development.

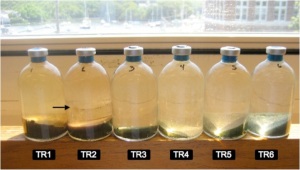

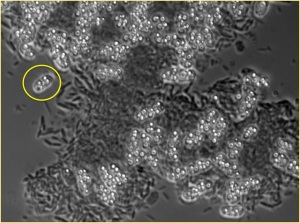

I mentioned that the flight surgeon in the room was using a different definition for reverse contamination. She was referring to the fact that, once the astronauts return to Earth, they are likely to have compromised immune systems and altered microbiomes. They may be at risk from exposure to common Earth microbes. I thought this was an interesting take on “reverse contamination.” Also, it brings up the topic of microbiomes, which is why I was in the room. I was there to talk about the microbiology of the built environment and share some of the results from Project MERCCURI’s microbial ecology of the International Space Station. The ISS represents an extreme built environment for a number of reasons, microgravity, high radiation levels, very little exposure to Earth air, very little flux of Earth microbes. The spacecraft that carries humans to Mars will experience extremes of those extremes. How will the microbiomes of the astronauts and their homes respond? Don’t worry, NASA is on that, too.